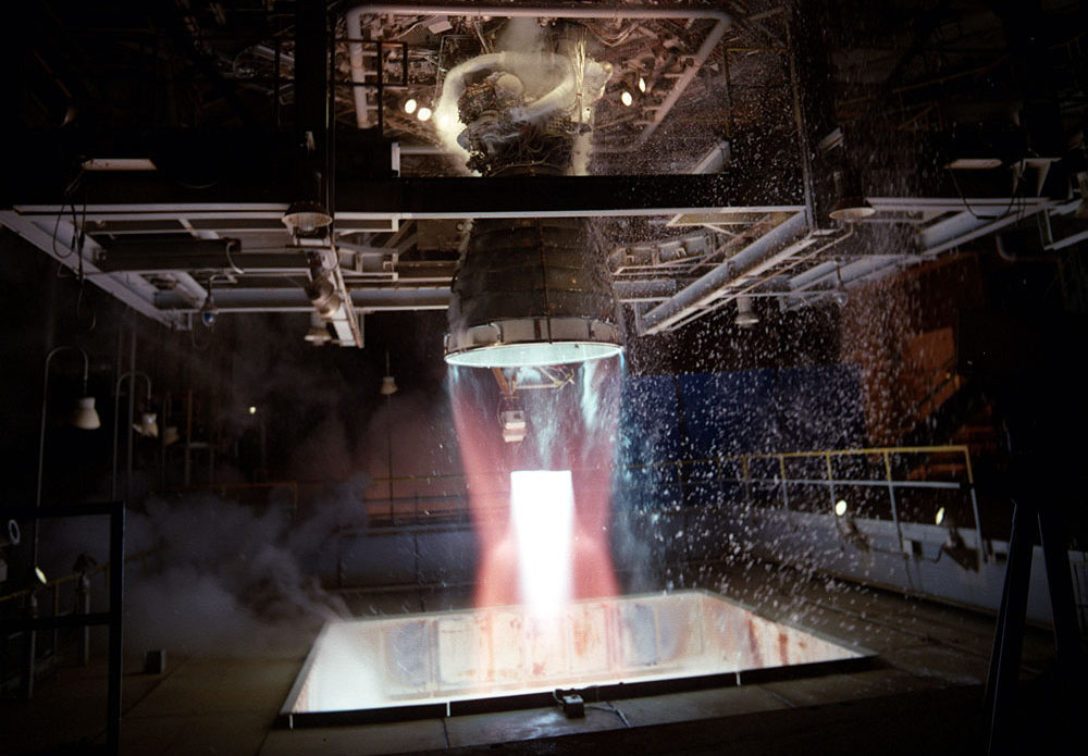

For nearly a calendar year, NASA’s Space Launch System has been undergoing a series of final tests at the agency’s Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. Routinely described as “exhaustive”, this eight-part test culminated this past Saturday afternoon with a test firing of all four RS-25 engines from the main core.

With a throaty thunder the RS-25’s, previous workhorses of the Space Shuttle and long considered a magnum opus in engine design, roared to life. And then, all too swiftly, they fell silent. That is not some metaphor of an author yearning for everlasting decibels from controlled combustion. It really was too short, approximately seven minutes short in test scheduled for eight.

The reasons are not yet clear. NASA staff from the flight test center mentioned an MCF (Major Component Failure), an opaque term implying a hardware failure. Stennis Director Richard Gilbrech seemed confident it was not a ground system problem, but rather something with the rocket. John Honeycutt, SLS Program manager, mentioned a flash around the thermal blanket system of the RS-25 rockets. Designed to protect each of the four engines from the fury of its brethren, the blanked was reconfigured from its original Space Shuttle configuration to provide better performance on the SLS.

However, it’s certainly risky to attribute to the failures of yesterdays test to any one system yet. More data will be analyzed, and the answer will be found. The question is the timing and expense in doing so. That latter question points to the more damning problem facing NASA, the SLS program itself.

Its nearly lamentable, and at least comical, to observe the differences in progress between SpaceX’s Starship/ Super Heavy program and NASA’s SLS. Both are heavy launch vehicles, with the former perhaps more ambitious in its design and goals. Despite this, SpaceX has consistently outpaced and outperformed its government counterpart development, despite a half decade advantage in time and ten billion dollars plus advantage in funding for SLS. This disparity looks to only grow worse, as the operational costs, how much it costs to launch each individual rocket, are set to be 2 billion plus for SLS, and potentially below 10 million for Starship. (This latter figure has been estimated even lower by Musk, although there are healthy reasons to see that as both extraordinarily optimistic and far out.)

But step back from SLS’s development performance and even leave aside credible if cringe inducing accusations of aeronautical job programs. What, exactly, is NASA even doing in the launch market at all? Certainly, when SLS kicked off in 2010 it had no true rival, and the only credible plans for a heavy launch vehicle were SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy. To doubt in a private companies’ ability to self-fund such a project was entirely understandable. But in 2021 A.D., not only has Falcon Heavy been flying for several years, and Starship making rapid progress, but Blue Origin with its New Glenn vehicle and ULA with its Vulcan Heavy variant all present legitimate, cost effective and highly performant options that are due for introduction right around when SLS is.

All those vehicles do lack in one key area. Customers. It is generally rare for missions demanding such large rockets to come around. SLS itself has only the Artemis program, and perhaps Europa Clipper (although even that mission is tentative to launch on SLS due to delays.) But NASA itself can serve to provide those emissions to its commercial partners. This enables not only better use of NASA funding, but the commercial entities to expand their capabilities, and refine their work, lowering costs and increasing the performance of their vehicles still further.

What could eighteen billion in U.S. greenbacks spent on SLS buy for NASA science? Let’s look at the four of the most recent and most NASA missions.

- Perseverance (Mar’s rover): $2.7 billion

- Juno (Jupiter probe): $1.1 billion

- Parker Solar probe: $ 1.5 billion

- New Horizons (Pluto probe): $780 million

Those four monumental efforts combine to around 6 billion dollars, including the cost to buy their own launch vehicles. NASA could have done those missions again, three times over, for what right now is a massively sized, massively performant, and entirely earth-bound launch vehicle.

The picture isn’t getting any rosier. Money has been spent that is never coming back. We don’t need to send more after it. NASA is legally bound to the whims of Congress and the budget it passes. It’s time for Congress to unburden the agency of this albatross.